Beyond Ballots: Reimagining Democracy in Bangladesh for Social Justice in Global Contexts

Real-world examples are plentiful. In the United States, the Electoral College system has been critiqued for creating situations where the popular vote is not reflected in the presidential outcome, as seen in the 2000 and 2016 elections.

Dhaka:

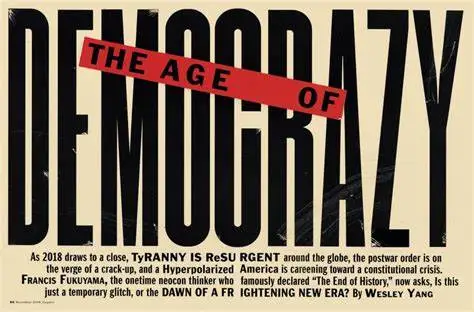

At the heart of this discourse is the premise that democracy, characterized by electoral processes and majority rule, has the potential to marginalize minority voices, leading to feelings of disenfranchisement and alienation. One could point to the phenomenon of “the tyranny of the majority,” a concept articulated by Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill, which describes a scenario where the majority’s interests prevail to the detriment of minority rights. The disillusionment among those who find their choices perpetually overridden in a democratic setup can indeed contribute to a sense of exclusion from the governance system.

Real-world examples are plentiful. In the United States, the Electoral College system has been critiqued for creating situations where the popular vote is not reflected in the presidential outcome, as seen in the 2000 and 2016 elections. This has sparked debates on the democratic legitimacy of the governance system and its implications for social justice. Similarly, the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom showcased a deeply divided nation, with the repercussions of the majority’s decision disproportionately affecting certain groups, thereby raising questions about the inclusivity of democratic decisions.

Another aspect of this discussion is the role of political parties and their conduct of post-election events. Victorious parties often have the tendency to reward their supporters, further entrenching divisions and potentially skewing policies towards partisan interests rather than the common good. This can lead to the erosion of social justice, as governance becomes more about consolidating power than ensuring equitable outcomes for all citizens. The ‘winner-takes-all’ approach can exacerbate social divisions and foster a political culture that prioritizes victory over virtuous governance.

Moreover, the cyclical nature of electoral democracy can lead to short-term policy planning, with governments focusing on immediate gains to secure reelection rather than the long-term systemic changes required for improving social justice. The intense focus on electoral success can detract from substantive policy debates and the implementation of justice-oriented reforms.

To address these concerns, political theorists like John Rawls have argued for a conception of justice that prioritizes fairness as the basis of a political system. Rawls’ theory of justice as fairness calls for a system where the basic structure of society is arranged such that it benefits the least advantaged members, which is often not the case in electoral democracies as currently practiced.

Furthermore, participatory democracy models, such as those advocated by Carol Pateman, suggest that a more engaged citizenry, involved in decision-making beyond just elections, could lead to governance that is more responsive to the needs of all, thereby enhancing social justice. Countries like Switzerland, with its direct democracy mechanisms, offer an example where citizens have more direct control over policy decisions through referendums and initiatives.

In considering the future of governance, innovative models like deliberative democracy, where reasoned debate and consensus-building replace majoritarian rule, might be explored as alternatives that can potentially bridge divides and foster a more just society. This would involve redefining political engagement, expanding it beyond the ballot box to include continuous dialogue and deliberation among all segments of society.

To truly redefine politics, governance, and state power in a way that aligns with social justice, a concerted effort is needed to reassess the values that underpin our political systems. It requires a commitment to inclusivity, a reimagining of political participation, and the establishment of mechanisms that hold governments accountable to social justice outcomes.

The utilization of Western electoral democracy as a political and philosophical tool by educationally, politically, and economically backward nation like Bangladesh further complicates the relationship between governance and social justice. In Bangladesh, ruling parties co-opt the language and mechanisms of democracy to legitimize their authority while simultaneously undermining the democratic processes and institutions that are essential for social justice.

Politically and educationally backward Bangladesh often face challenges in establishing the robust civil societies and informed electorates that are essential for a functioning democracy. In such contexts, electoral democracy is reduced to a mere formalism, with elections serving as a façade for authoritarian practices. This undermines the very essence of social justice with active and informed participation by the citizenry.

For example, consider the concept of “illiberal democracy,” as seen in some Eastern European countries, where democratic institutions are ostensibly in place but are manipulated to entrench the power of the ruling elites. These regimes may maintain the outward appearance of democracy through elections, but they systematically erode civil liberties, restrict political dissent, and manipulate electoral processes to ensure their dominance.

Bangladesh, grappling with poverty and inequality, finds that electoral democracy does not necessarily translate to equitable development. Here, the ruling parties exploits the electoral system to prioritize policies that benefit the elites or their political base, rather than addressing the structural inequities that plague our society. The prioritization of populist measures over substantive economic reforms exacerbates disparities and hinder the realization of social justice.

In Bangladesh, the concept of social justice is often politicized, with ruling parties using the promise of justice to garner votes while failing to implement the systemic changes needed to address deep-seated injustices. The political discourse surrounding social justice becomes a means of rallying support, with little genuine commitment to the hard work of building equitable institutions and societies.

Moreover, the influence of external actors, including former colonial powers and international corporations, are skewing the priorities of Bangladesh. These influences often reinforce a narrow conception of democracy, emphasizing electoral processes over the broader democratic principles of accountability, transparency, and inclusivity. As a result, the potential of democracy to serve as a vehicle for social justice is compromised, and the concept becomes a tool for maintaining the status quo rather than a means of transformation.

To counter these trends, there is a need for a reimagined approach to democracy that is sensitive to the unique challenges of educationally, politically, and economically backward nation like Bangladesh. This approach would emphasize the development of local democratic institutions, the strengthening of civil society, and the fostering of an informed and engaged electorate. It would also require a commitment to social justice that goes beyond electoral cycles, encompassing sustained efforts to address inequality and promote the well-being of all citizens.

In this reimagining, the international community has a role to play in supporting the development of genuine democratic governance structures that can advance social justice in Bangladesh. This support must be based on respect for the autonomy and cultural context of Bangladesh, avoiding the imposition of external models that may not be appropriate or effective.

Ultimately, the challenge is to create governance systems that are both legitimate and committed to the principles of social justice. By integrating theories of justice, participatory mechanisms, and accountability frameworks into the governance model, it is possible to envision a political system that not only represents the will of the people but also upholds the dignity and rights of all citizens. This transformation is not only imperative but also achievable through the collective will and concerted actions of a society committed to equality and fairness.

Written by Rajeev Ahmed

Geopolitical Analyst, Strategic Thinker and Editor at geopolits.com