Nepali quest for meaning

The greatest strength of Nepali democracy should be our openness and tolerance to hear each other’s opinions.

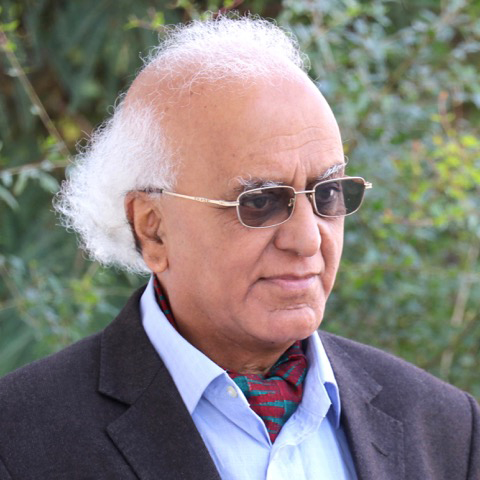

By Abhi Subedi

This is an essay about our quest for meaning. Kathmandu occasionally gets into a mood to see politics doing some miracles for this. Holding peaceful demonstrations and expressing opinions through media and books is a spontaneous process of democracy. The organisers of events naturally hope to create some impact by imitating the big uprising events in history. Every country’s history is full of efforts made by people to emulate such events. A history that has covered some familiar courses shapes the pattern of politics. Each course has its own narrative. In Nepal, too, the patterns of history maintain their continuum in various forms. As history has some citational features, we can refer to some events of modern Nepali history, as below, to understand our quest in the present.

The feudal system or the Rana oligarchy, which ended in 1950 after 104 years, has always maintained its presence in our behaviours; its spectres continue to affect our psyche in various ways. The great political events of contemporary times, like the people’s uprising of 2006, the abolition of monarchy in 2008, and the promulgation of the federal republican constitution in 2015, all being recent events, get naturally reviewed at every turn of events. British modern poet TS Eliot puts such character in history in his famous poem “Gerontion” (1919): “History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors and issues.” The famous Peace Treaty was signed among the nations involved in the First World War when he wrote this. Nepali poets, too, have written about the effects of the important events of contemporary times. As this is not a literary article, I do not want to explain that.

Personas that led the system and assessed its effect are naturally putting forth their efforts to bring changes. Events happen. For example, two different factions who espouse different visions of history are at loggerheads in some public places in Kathmandu while I am writing these lines. Politics naturally shapes the pattern of our quest for meaning at the individual and social levels. Nepali history and events shouldn’t always be viewed in isolation. We should link our efforts and achievements to what is happening and will happen not only in our part of the world but also in other countries. It is necessary to learn to see our activities in broader contexts, too. I would like to allude to the following news commentary as an example.

I was struck by a short but very eloquent commentary written by Zanny Minton Beddoes, Editor-in-Chief of The Economist, on November 13, 2023. She gives a simple but astounding calculation that more than half of the people on this planet will hold nationwide elections in 2024. Calculating from the voter turnout pattern, she estimates that nearly 2 billion people in more than 70 countries will cast their votes that year. She says, “This milestone has been reached for the first time”. The staggering figure covers all the world’s major countries, including our region. Beddoes’s short commentary frankly says that democracy will not be “triumphant” in these elections. This is a subject of debate and studies that have already started earnestly. In this short essay, I want to look at some response patterns and activism triggered by the indications of such analyses.

All indications suggest that the 21st century has entered a new phase of the quest for alternate meaning about life, state management and governance. Though it is a familiar pattern maintaining a continuum since ancient Greek times, its application in an age that has seen unprecedented transformations is both alarming and encouraging. However, theorists, philosophers and pragmatists have not realised the ecological damage caused by human actions happening on a colossal scale. But I am more concerned about our responses to the transformations from the second decade of the 21st century.

Where do we stand in all this? The answer is not easy. We ask naturally, are we caught in the course of events or global trends, or are we trying to construct our patterns for our own advantage? One thing is certain: People of big or small nations, weak or powerful, can choose their system and architect their models of prosperity. In Nepal, we can experiment with political systems and structure our society so that no group or groups dominate the others. The most crucial point in this is self-realisation. It may sound ethical or spiritual, but what can be said from our failings is that we or our political parties, institutions, and people who run the organisations in the country have been failing on an important score—they lack idealism for work, a realisation and an honest commitment to one’s action.

For someone like me who still keeps Eric Hobsbawm’s book The Age of Extremes (1994) within easy reach for its analyses and tremendous information, it is natural to hear alarm calls such as those mentioned above to look into the other side of reality. But then the concepts of post-truth or alternative reality and other such perceptions of postality are misleading and obscurantist. Judging in the context of global political trends like those under review here, we should look at ourselves and judge our perceptions of politics and the constitutional system. We should ask ourselves where we stand in matters concerning democracy vis-à-vis a dictatorial system of government. This question holds great importance, especially when the democratic systems of the world are experiencing unprecedented changes and even threats.

As a literary writer, my perceptions about freedom are shaped by a faith in the power of free expression and the importance of humanistic values. I believe that is the mantra of democracy. But I have great faith and trust in the hard-earned democratic system. History may repeat, but when it repeats, it brings the messianic effects of the past, in the words of a great thinker, Walter Benjamin.

The greatest strength of Nepali democracy should be our openness and tolerance to hear each other’s opinions. Our quest for meaning can be realised only in democracy and the free and peaceful expressions of opinions. This should be the mantra of action for our survival and prosperity.

Abhi Subedi is a poet, playwright and a columnist.