The US needs India to buffer China, and Modi knows it

Biden had an ideal of putting human rights at the center of American diplomacy, but he’s running into hard reality.

The killing of a Sikh separatist in Canada in June, allegedly by agents of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Indian government, has opened a rift between one of America’s closest allies and one of its most vital geopolitical partners. It has also illustrated an unavoidable irony of President Joe Biden’s foreign policy.

Biden aims to bolster a threatened global order by hastening India’s rise. As India rises, however, it will act in ways that sometimes challenge the very order Washington must defend. And if Biden’s team believes, as Asia policy czar Kurt Campbell has said, that the US and India have “the most important bilateral relationship on the planet,” then Washington will probably tolerate a lot of bad behavior to keep that relationship intact.

The geopolitical case for US-India cooperation is unimpeachable. Way back in 1904, British polymath Sir Halford Mackinder explained why.

Thanks to the modernisation of both technology and tyranny, he wrote, there was a growing possibility that aggressive powers would dominate Eurasia and control its unmatched resources. So the era’s liberal hegemon, Great Britain, must cultivate “bridge heads” on the edges of the supercontinent — Korea, France and India — so it could keep the world in balance by keeping Eurasia divided.

Today, large swaths of Eurasia are ruled by US enemies — a prickly, bellicose China; a vengeful, violent Russia; an expansionist Iran. India, an increasingly prosperous country of 1.4 billion people, may be the key to holding the balance — and particularly to denying China a free hand on land as it also expands at sea.

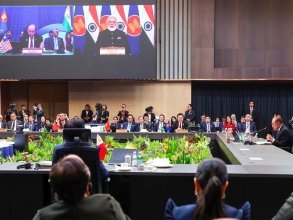

India is no less critical as a global manufacturing hub, a contributor to resilient technological supply chains, and a diplomatic leader of the developing world. This is why Biden has so prioritised strengthening US-India relations by hosting Modi for a state visit in Washington, helping make the recent G-20 meeting a showcase for Modi’s leadership, and pursuing deeper cooperation across the board.

Yet Biden doesn’t view India as a prospective military ally; he isn’t counting on New Delhi to rush to America’s assistance in a war with China over Taiwan. The idea is simply that America and India share a vital interest in keeping Beijing from dominating Asia and, perhaps, the world. So the US helps itself by helping India develop economically, mature militarily, and otherwise put its power athwart China’s path to primacy.

It’s not all upside. A US president who initially talked about a great clash between autocracy and democracy has taken a very muted approach to discussing the infringement of human rights, civil liberties and political freedoms in Modi’s India — or the incendiary Hindu nationalism in which his government traffics.

Likewise, India hasn’t done much to punish Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In fact, it has benefitted greatly from the war, which allows it to obtain Russian oil at discount rates. And if indeed Modi’s men killed Hardeep Singh Nijjar in Canada in June, his government is emulating the transnational repression associated with harder-edged autocracies like China, Russia and Saudi Arabia.

The trouble with tying oneself to quasi-illiberal governments is that they tend to do the very things Washington deems corrosive to the liberal order. Indeed, if India is an indispensable partner, it remains deeply ambivalent about the system Biden means to preserve.

India opposes Chinese hegemony, but that doesn’t mean it loves American might. New Delhi wants a multipolar system, in which India stands among the great powers, rather than a unipolar system in which Washington and its allies tower above the rest. And as India’s influence grows, it will demand great-power prerogatives — including, perhaps, the right to trample the sovereignty of other democracies by targeting domestic enemies on their soil.

Right now, Modi’s government believes New Delhi holds all the cards. Indian officials have privately said they just don’t believe Washington will do anything to spoil the relationship, given how desperately America needs support against Beijing. They’re probably right.

This dilemma will govern Biden’s response to Nijjar’s murder. When Russian agents poisoned one of Putin’s enemies on British soil in 2018, there was a coordinated Western response featuring mass expulsions of Russian diplomats. Canada isn’t going to get a similar level of solidarity.

This dilemma will govern Biden’s response to Nijjar’s murder. When Russian agents poisoned one of Putin’s enemies on British soil in 2018, there was a coordinated Western response featuring mass expulsions of Russian diplomats. Canada isn’t going to get a similar level of solidarity.

To be sure, the US is helping: American intelligence reportedly helped establish India’s complicity. But the US also reportedly asked the Canadian government to slow-roll its public accusation — even as Biden raised the issue with New Delhi behind closed doors — to avoid ruining Modi’s star turn at the G-20. Expect the Biden administration to privately tell New Delhi that this sort of extraterritorial repression is unacceptable — and to try hard to avoid any further public spat. Whether Modi listens is another matter.

A deteriorating global situation makes the US increasingly dependent on imperfect partners that are wont to do unpleasant, even brutal things. There is no answer to Chinese power without a more assertive India — and no avoiding the fact that Washington won’t always like what such an India does.

Hal Brands is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist and the Henry Kissinger Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.